A best practice guide for authors

It is based on the discussions during BMJ’s roundtable on capacity to consent. It includes contributions from clinicians, ethicists, patient representatives and lawyers with significant expertise on this topic.

We also considered relevant legislation. As an international publisher with our head office in London, we refer to England and Wales legislation, i.e. the Mental Capacity Act (MCA), 2005, 2007. We see this legal baseline as the minimum standard.

Above this legal baseline, publishers and authors have ethical responsibilities towards patients and subjects of research such as those outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and

the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity.

As a publisher and global healthcare knowledge provider, at BMJ we must make sure that proper consent for publication has been obtained by the authors and that the individual(s) involved is/are aware of the possible consequences of publication.

As authors submitting manuscripts for publication involving human subjects, you must ensure the individual(s) involved is/are aware of the planned publication and has given their consent as early as possible.

You also have an ethical and legal duty to consider the individual's capacity to consent on their own behalf when obtaining consent for publication. All four elements of consent are equally important, namely;

i) capacity;

ii) sufficient information;

iii) voluntariness; and

iv) the ongoing or continuing nature of permission.

We often find that authors have confused consent for publication with consent for participation in their study. For the purpose of this document, "consent" refers to consent to publish personal information about an individual, and not informed consent for participation in a study.

Some consent forms for participation in research do cover intended publication, however, these forms rarely meet BMJ's requirements, ensuring the individual has been fully informed of the benefits and harms of publication. Consent for participation in research still must be obtained according to appropriate ethical standards.

The best way to ensure you have obtained appropriate consent for publication in one of BMJ's journals and prevent delays in the editorial process is to use our BMJ consent form. This includes a detailed description of what is involved and sharing of that publication. It is a requirement for publication in any BMJ journal, and available in multiple languages. While we are happy to consider alternative consent forms, you should be aware that they rarely meet our legal requirements for publication.

You should also confirm that the original copy of the signed form is held by the treating institution should any queries be raised in the future. Assessing if your manuscript requires consent for publication

At BMJ, we require a signed BMJ consent form for any manuscript (or other content) that includes identifiable information about an individual.

Identifiable information is any personal information about an individual, patient or participant in research that can be identified as belonging to, or likely to belong to, a particular

individual.

Case reports, small case series or referring to individuals in commentary or personal observations are most likely to contain identifiable information and require consent. Aggregated data is not usually considered to be identifiable, however be wary of small numbers which might effectively make this information identifiable. At BMJ, we consider groups of less than 5 to be identifiable.

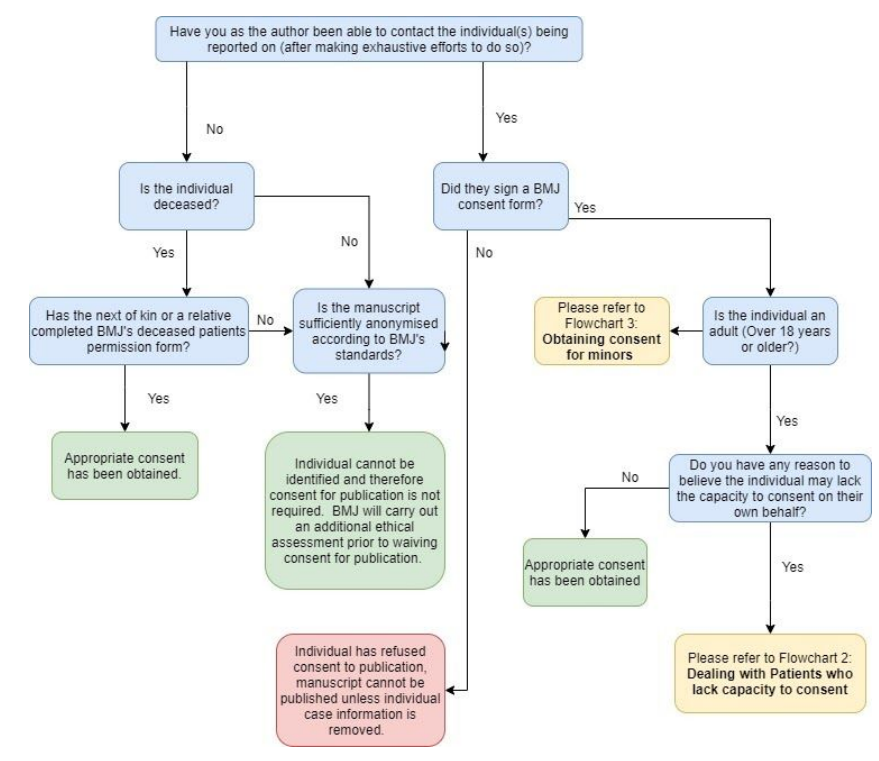

Figure 1: Flowchart depicting standard procedure for consent for publication.

Figure 1: Flowchart depicting standard procedure for consent for publication.

How to proceed if the individual cannot be contacted

It is BMJ’s view that confidentiality and “true anonymisation” can never be 100% guaranteed. This is particularly the case given the increasing general availability of data in the public

domain including social media platforms.

If you want to submit your manuscript without a consent form, you must ensure that your manuscript is sufficiently anonymised according to BMJ’s anonymisation policy. See: How to check if my report is sufficiently anonymised. Some journals and article types will not consider articles without a consent form, whether they are anonymised or not.

Obtaining consent for publication

i) capacity;

ii) sufficient information;

iii) voluntariness; and

iv) the ongoing or continuing nature of permission

When seeking consent, you must ensure you give the individual sufficient information about the content of the material to be published, including providing them a copy and discussing

the implications of publication.

This includes explaining that others may reuse and republish the information, it might be made widely available via the internet and that we cannot guarantee anonymity though alsos

should always remove identifiable personal information where possible.

BMJ’s consent form requires the individual to confirm they have seen any material about them prior to providing their consent and clearly outlines any important information to give

people, before asking them for consent to publication.

It is important that the individual is able to make a decision freely with regard to their own thoughts and feelings about publication without being overly influenced by others.

This is especially important if an author has a relationship with the individual e.g. is their treating clinician and the individual may feel that his or her care could be influenced by their

decision about publication.

Questions for authors to ask themselves and individuals include:

Is the individual making a free decision about publication?

What influences might there be on the individual’s decision regarding publication?

Do they understand that agreeing or not agreeing to publication will not affect their care?

You should keep in mind the following principles when assessing if individuals have the capacity to consent:

1. The law in England and Wales presumes that all adults have the capacity to consent. Where the behaviour of the individual makes us unsure if they can consent, the law still requires that we presume the person has capacity and incapacity must be proven (Mental Capacity Act 2005, 2007).2. The focus should be on exploring the individual's ability to make a specific and informed decision about publication

3. The best outcome is that the individual, where possible, is supported to make their own decision about the proposed publication

4. Capacity to consent for participation in treatment does not necessarily mean that the individual has the capacity to consent to publication. Decisions around releasing confidential information often require more complex decision making than decisions related to treatment.

5. Whether an individual may temporarily or permanently lack capacity is an important part of assessing capacity. It is unhelpful to put “individuals who lack capacity” into one broad category; each individual and the specific decision should be considered carefully.

Is there reason to doubt the individual’s ability to consent?

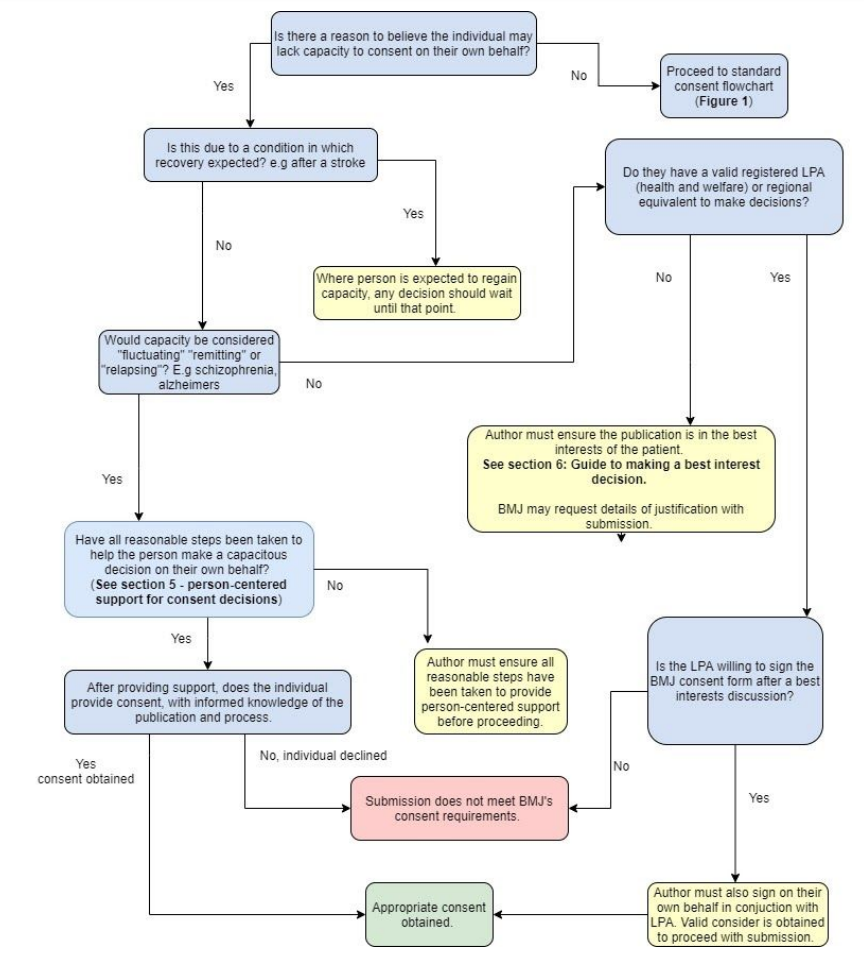

When assessing whether the individual has capacity to consent on their own behalf, we advise asking the following questions (see also: Figure 2: Flowchart for authors on assessing capacity to consent).

Providing person-centred support to help with decision-making

Authors must provide all practicable support as necessary and appropriate to help an individual to make their own decision.

This support must be person-centred. It cannot be assumed that all individuals with the same condition should be treated the same: be guided by the individual.

We recommend the following:

BMJ’s guidance allows proxy consent in certain situations where an individual is not able to consent on their own behalf and is unlikely to ever be able to do so. But it bears repeating that individuals should always be supported to make their own decisions, if possible.

If you plan to obtain proxy consent, then consider the following:

You (as the author) are responsible for doing everything you can to help the individual to participate in making a decision about publication and to determine what is in their best interests

Figure 2: Flowchart for authors on assessing capacity to consent

Figure 2: Flowchart for authors on assessing capacity to consent

Ensuring the publication is in the best interest of the individual

When thinking about what t is in the best interests of the individual, you should remember the following:

To what extent does publication serve public interests?

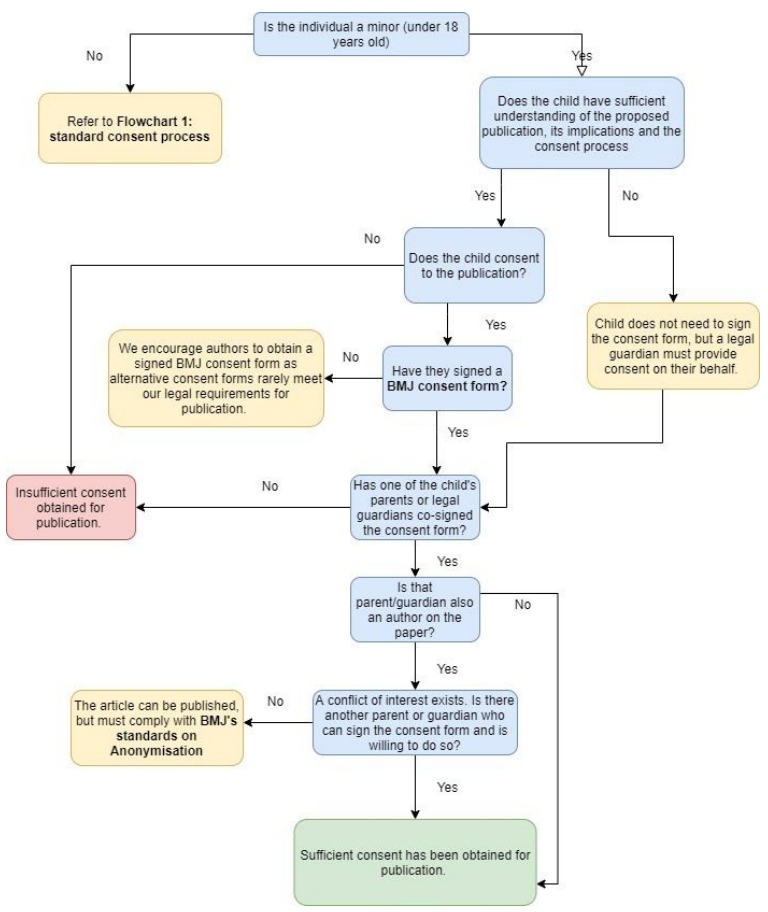

Children are a vulnerable group and as such BMJ has strict consent standards for papers that report on children. For publishing purposes, we consider individuals under the age of 18

to be children.

As with adults, you must think about i) their capacity; ii) providing sufficient information; iii) voluntariness; and iv) the ongoing or continuing nature of permission, when you obtain

consent for publication.

Children who have the capacity to consent to publication

Individuals of any age may have the capacity to consent to share their confidential information. We advise that you engage the child in making a decision about publication. If they can understand the information provided and are able to voluntarily make a decision, then children can consent to publication.

Where the individual is under the age of 18, we require parents or guardians to provide consent as well.

We recognise that this differs to clinical practice in England and Wales where 16 and 17-year-olds can provide consent without their parents and there may be 16 and 17 year olds who want

to share their personal information without involving their parents, as the publisher we will consider the decision to publish these on a case by case basis

Principles

If the child has the capacity and does not give their consent to publication then it is BMJ policy that we will not publish, even if their parents or guardians consent.

If the child has the capacity and consents to publication but the parents or guardians refuse, then we consider these on a case by case basis.

Children who do not have capacity to consent to publication

A child’s default proxy is the person who has parental responsibility or their legal guardian. A parent or guardian is able to give consent on behalf of a child who lacks capacity, as long as publication is in the best interests of the child. As an author, you must consider whether publication is in the best interests of the child and whether their parent or guardian has given sufficient consideration to the benefits and harms. It is important to recognise where a child may come to regret the decision of publication in the future and all material should be anonymised where possible to minimise this risk.

If the childs’ parents or guardians disagree with each other about whether they should consent to publication then BMJ will consider whether to publish on a case by case basis.

Figure 3: Process for obtaining consent for minors

Figure 3: Process for obtaining consent for minors

BMJ’s consent policies are managed and upheld by BMJ’s research integrity team. BMJ’s consent policies are designed to protect patient confidentiality while at the same time supporting the communication of important medical and scientific information. We balance these two aims in a way that delivers on our vision of helping to create a healthier world.

We know that ethics is rarely about absolutes, context matters, and judgment is essential and we often consult the BMJ ethics committee on individual cases to ensure a high standard of publication ethics.

We assess the scientific value of the submission along with benefits and harms discussion, to ensure the following:

We may ask authors to provide any necessary information in order to enable us to make that assessment.

We would like to thank the participants of BMJ's roundtable on the capacity to consent for their input into this guidance and for reviewing the final document.

References:

1. BMJ Roundtable on the capacity to consent (for publication). (2021) figshare. Online

resource. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13468818.v2

2. Consent to publication | The BMJ. Available at: Consent to publication

3. 2005. Mental Capacity Act 2005. 1st ed. [ebook] Legislation.gov.uk, p.Section 16A.

Collated by the BMJ Research Integrity team: Simone Ragavooloo and Dr Cat Chatfield

View this information in PDF format.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.